The impressive report, Public vs. Private Sector Compensation in Ohio: Public workers make 43 percent more in total compensation than their private sector colleagues (the Report), by 2 highly qualified PhD economists comes to an amazing conclusion. How did this big of a disparity come to exist?

Reading the 1st conclusion in the executive summary raises a red flag:

- actual take-home pay for public employees is 2.5% less than for comparable private workers

Deeper in the Report, actual out of pockets costs for public and private benefits are listed (but not summarized) which are similar to those in a recent study that ranked Ohio Public Employee Retirement System (OPERS) benefits in the middle of the pack of the 15 largest Ohio private employers. Here’s how the out of pocket from each lines up:

|

Out of Pocket Costs – Public Versus Private Retirement % of Salary |

|||

|

The Report Average of all Corporations |

Ohio 15 Largest Private Employers |

OPERS Taxpayer Contribution |

|

| Social Security |

6.2% |

6.2% |

0 |

| Retirement Plans |

6.0% |

7.6% |

14% |

| Total |

12.2% |

13.8% |

14% |

All of the difference in compensation is due to valuations of benefits compared to private employers, not actual out of pocket costs. The Report’s conclusion is not that the costs of Public Employees’ Benefits are that much different than Private Employees but that Public plans deliver much more value for the buck than Private plans.

This Report breaks new ground in trying to calculate the value of public sector retirement benefits compared to private sector benefits. The 43% higher compensation in the title is from two separate calculations: 11.8% for the value of Public employees’ job stability and 31.2% for “fringe benefits”.

Valuing job stability is difficult as there is no actual out-of-pocket cost to tax payers or performance penalty to act as a baseline plus there are serious issues and outdated assumptions in the Report calculations. First, 10 of the 11.8 percentage points are from an assumption that public employees would have to take a job with lower total compensation (wages and benefits) if they went in the private sector even though public employees make less take home pay and the higher benefits are being counted in the 31.2%.

Hmm? Isn’t this an unrealistic “Scrooge” pay plan that counts an imaginary 10% cut as part of your compensation? Never mind, let’s just agree to throw this 10% out as double counting.

Public employees’ greater job security was valued at 1.8% of compensation based on unemployment differentials that the report did not adjust for the “switching” from public to private employment. In any case, there is no premium from public job security today: Government is predicted to continue cutting jobs while the private sector is growing. In October 2011, government shed 24,000 jobs while private employers added 104,000 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Report concludes “when pay and benefits are taken into consideration public workers receive 31.2 percent more in total compensation than private sector counterparts%.” There are 2 areas that need to be investigated to figure out if the report is right:

- What is a “private-sector counterpart” and is this comparison correct?

- The report compares public employees to the average for full time employees at medium to large private employers. This appears reasonable.

- The comparison calculates the difference in ““pension compensation” which represents the present value of future employer funded pension benefits accrued in a given year of employment.” The calculations in large part depend on the fact that public employees have defined benefit programs while most private employees have defined contribution programs.

- This difference between defined-benefit programs at private and public employers has mostly arisen since 1980 so this comparison shows how much compensation private employees have lost since 1980 – if the calculations are correct. The Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) has compiled historical retirement plan data, though the early years are slightly different for public and private data. Plan coverage for full time employees at medium to large private employers has declined from 91% in 1985 to 66% in 2010 while public employee retirement plan coverage declined from 98% in 1987 to 94% in 2010. Defined benefit plan coverage for private employers had declined from 84% in 1980 to 30% in 2010 while Public employee coverage by defined benefit plans has only declined from 93% in 1987 to 87% in 2010. This data is summarized in the table below.

| Plan Type |

1980 |

1985 |

1987 |

2010 |

||||

| Private | Public | Private | Public | Private | Public | Private | Public | |

| All retirement |

N/A |

N/A |

91 |

N/A |

N/A |

98 |

66 |

94 |

| Defined benefit |

84 |

N/A |

80 |

N/A |

N/A |

93 |

30 |

87 |

| Defined contribution |

N/A |

N/A |

41 |

N/A |

N/A |

9 |

54 |

19 |

Source: EBRI compilation of the US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics data

- Is the calculation that public employee benefits are 31.2% greater value than private benefits correct? If not, what is the true difference?

- The 31.2% is based on using an “ivory tower” riskless rate of return rather than actual, “real world” investment returns to calculate the value of Social Security benefits and future liability for Public retirement plans. The note below goes over the paradox that “risk free” securities are not free of investment risk. As benefits are paid in the real world, real world rates of return are appropriate.

- Social Security benefits and returns are mandated by Congress rather than based on investment returns so there is validity to the fact that Public retirement plans investment returns are better than Social Security. The Report calculated this to be an effective 4.2% reduction in private employee compensation based on the riskless rate of return. The actual difference is greater as Public retirement benefits result from actual rates of investment return. There was a major adjustment down in SS benefits in 1982 (rather than an adjustment upward in returns) to match income and liability so most of this difference is the result of a reduction in benefits to private employees.

- The remaining 27% difference is not valid because it is based adjusting Public plan benefits to reflect an “ivory tower” riskless rate of return rather than a real world actual rate of return on investments. As benefits are paid in the real world and there is no evidence that Public retirement plans to use an incorrect rate of return, there is no basis for increasing public compensation to cover retirement plan shortfalls.

In summary, it appears that the Report reveals that Private employees are similar in total out of pocket benefit costs to Public employees but the value of benefits received is greater for Public employees. The majority of this difference is due to the congressionally mandated lower return on Social Security contributions.

An unanswered question is whether the major shift of private employers from defined benefit to defined contribution retirement programs has resulted in additional reductions in private versus public employee benefits.

* Note on the Report’s calculation of retirement benefit costs.

The question here is whether the “risk free” rate or the rate of anticipated return, as is currently done, should be used as a discount rate for public defined benefit plans.

The comparison is made to private plans which use the more conservative corporate bond rate rather than the estimated return on investment. The reason the rate is specified for corporations is so they cannot manipulate the rate to increase their profits by lowering their required contribution. Public entities don’t have this “profit” motive that is proven to lead to so much abuse. There is no proof that there is a widespread problem with public pension plans using improper rates of return while there are many examples of improperly funded private plans.

The statement in the report that “For these purposes, however, all that matters is that the accounting be made consistent between different pension types” is totally incorrect as the dangers of abuse to each plan are significantly different. Accounting standards are designed to eliminate potential misstatements and abuse. Financial analysis is needed to establish whether there is adequate funding and accounting standards’ requirement of eliminating abuse can and do conflict with getting the best possible financial statements.

Using the “risk-free” rate cannot give a clear picture of the financial status of a retirement plan. First, you need to understand that the “risk-free” rate is not actually free from risk. “Risk-free” securities are free from default risk. Default risk is the risk that the company or country will not be able to pay when the security comes due. Because the U.S. Government prints dollars, the possibility that it will default on its bonds is zero so they are “risk-free”. (Even Congress cannot default on these debts as the 14th amendment states “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”)

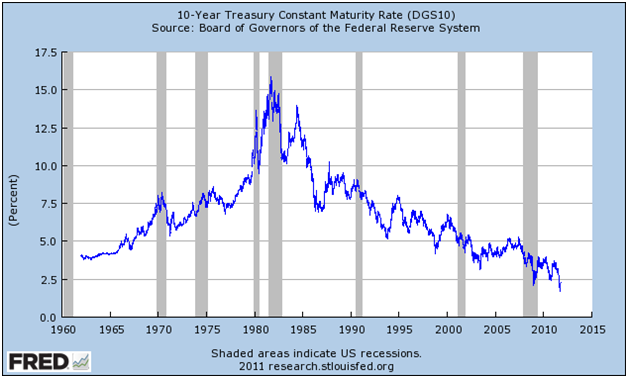

But default risk is very small for any investment grade security – that is why they are “investment” grade. The real risk for any bond is interest rate risk. Even government bonds have interest rate risk; in fact, interest rates changes often make government bonds prices more volatile than the stock market. The chart below shows the “risk-free” rate on the 10 year Treasury bond from 1960 to the present. As you can see rates have varied from over 15% down to the current rates of below 3%, a 5 fold range.

The wide, year to year swings in interest rates has resulted in significant problems with private plan funding which are being partially addressed in proposed international accounting rules. The rate of anticipated return does not have the skew caused by wildly varying interest rates and is preferred on a financial basis when the entities involved are trustworthy. History has shown that governments are much more trustworthy than corporations in financial reporting and accounting standards reflect this. New proposed Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) rules have affirmed this is appropriate for existing public defined benefit plan assets with discussions purely focused on how to report funding shortfalls.

Finally, there’s no proof that Ohio pension plans are significantly underfunded on a long-term basis as alleged in the Report. The cited Congressional Budget Office report, “The Underfunding of State and Local Pension Plans” (May 2011), looked at the funding gap that occurred in 2008 and 2009 during the depths of the recent recession when asset prices were depressed. Since that time there has been a recovery in asset prices that has closed most if not all of the gap.